When leader of the opposition Jeremy Corbyn took to the despatch box on Wednesday afternoon to quiz the prime minister on solar cuts, it almost felt like a landmark moment.

Any mention of renewables during Prime Minister’s Questions is almost as rare as a straight answer from the Department of Energy and Climate Change, so to see the Labour leader drag the issue into the mainstream was pleasing to see. That Cameron’s answer conveyed a complete ignorance of the issue at hand was unsurprising, but almost secondary.

Unfortunately – or perhaps fortunately given the chancellor’s current attitude to renewables – that was to be the only mention of solar that day. George Osborne delivered his autumn statement and spending review from 12:30 onwards and merely gave energy a passing reference as he reeled off policy after policy, all designed – he said – to stimulate the economy.

“For we are the builders,” Osborne repeatedly exclaimed, seemingly oblivious to the sheer number of jobs that were lost from the construction industry in the wake of economic and housing crises. The builders, George, have since had to try their hand at other trades.

With changes to the RO and feed-in tariff still under consultation, concrete announcements on energy policy weren’t forthcoming. The future of the renewable heat incentive was confirmed and ECO was indeed extended out to 2022, but their precise workings have yet to be disclosed. Energy secretary Amber Rudd gave her landmark energy statement last week and Osborne stole none of her thunder.

There were, however, a few fleeting glimpses into Osborne’s workings. DECC’s budget was revealed to have been cut by 22% over the four years – £220 million of savings is to be realised from cheaper contracts and the “pooling” of back office services.

The department was seemingly rewarded for its good work to date and has had its innovation fund doubled to £500 million. While storage could benefit, nascent nuclear technology will undoubtedly command much of that fund. Small-modular nuclear reactors are the flavour of the month within DECC and could not be thought of any more highly by Rudd if her evidence before the ECC select committee earlier this month was anything to go by. As Rudd’s predecessor Ed Davey put it at an event yesterday, there’s a nuclear reactor coming to a town near you soon.

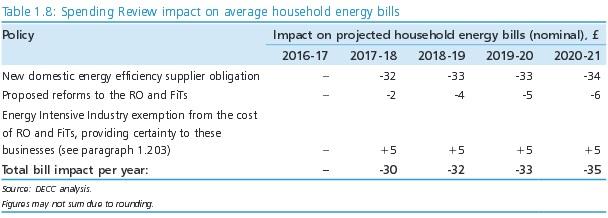

But arguably the most galling announcement from solar’s perspective was pitched as a rescue package for the UK’s much beleaguered steel works and other energy-intensive industries (EII). EIIs will no longer have to foot the cost of renewable energy deployment and will be made exempt from paying levies on their energy bills going towards the RO and FiT incentive schemes. This cost will instead be diverted onto household bills at a cost of £5 per household each year, as the Treasury’s CSR document revealed.

Over the four years 2017/18 to 2020/21, that will cost consumers an extra £20 – less than the £17 the government looks set to save consumers by scrapping the RO and feed-in tariff in the same period.

The government and DECC in particular has billed cuts to the feed-in tariff as absolutely vital in order to protect consumers from higher bills, but just months later have heaped on more costs to effectively offer state aid to high-energy consumers. It begs the question, what does DECC constitute as an acceptable reason for driving up bills, and where does it draw that line? It’s of little wonder former shadow energy secretary Caroline Flint labelled recent policy decisions as “economically illiterate” hours before Osborne’s address.

With so few precise details forthcoming from HM Treasury this week – documents are expected to continue to be drip-fed over the coming days – the energy sector in general remains almost in a state of flux. Solar remains braced for the outcome of the feed-in tariff consultation, after which there will be a lot more certainty.

But the type of policy incoherence that Osborne has conveyed – that the government is eager to reduce bills one second, but increase them the next – is precisely the kind of uncertainty that is angering developers and deterring investors. It’s of little wonder that the prime minister cannot give a straight answer on solar to the leader of the opposition if those serving him cannot come up with a straight policy in the first place.