The High Court handed down judgment in Ross v Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government and Renewable Energy Systems Ltd 2025 EWHC 1183 (Admin) on 23 May 2025.

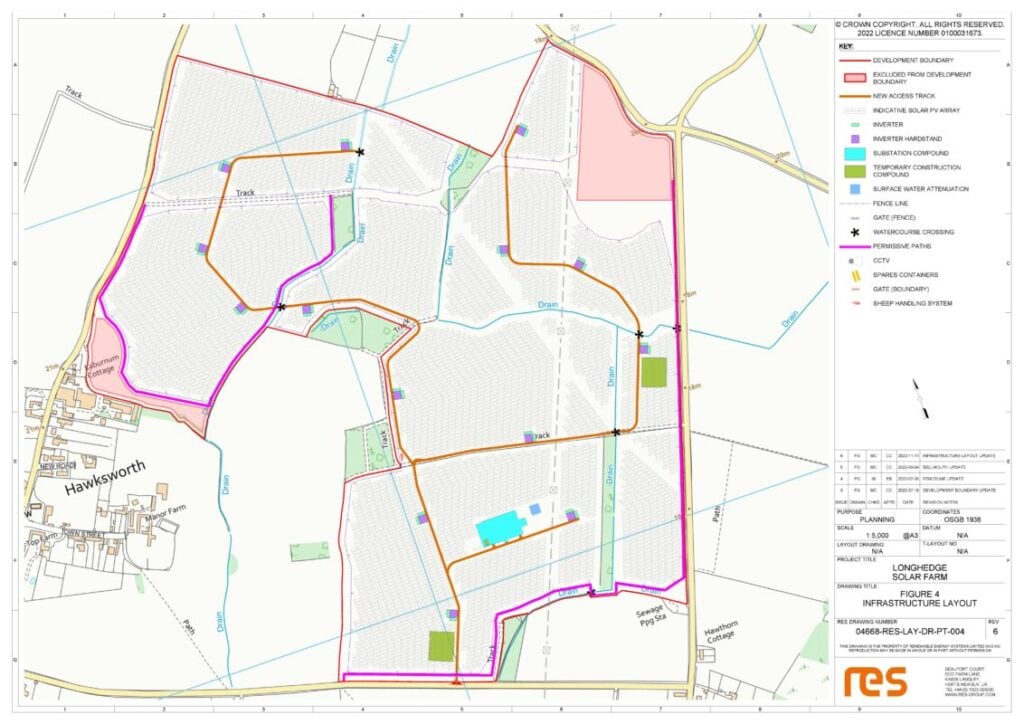

This case concerned the Longhedge Solar Farm, an energy project proposed by Renewable Energy Systems Ltd (RES). The Local Planning Authority (the claimant) refused planning permission for the solar farm, and RES was successful at appeal. The claimant then challenged the Inspector’s decision in accordance with section 228 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990.

The main issue considered by the High Court was the interpretation of the provisions of the National Policy Statement for Renewable Energy Infrastructure EN-3 (NPS EN-3) in relation to “overplanting” solar panels and the number of solar panels that can be installed on a site technically capped at 49.9MW of export capacity.

The 49.9MW capacity figure is of particular relevance as it is just below the current 50MW capacity threshold for a solar farm to be classified as a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project).

Overplanting

Overplanting means installing more generating capacity (in development control terms) than the site is allowed to export to the grid (in alternating current or “AC” terms); or more simply, installing more solar panels than is actually required.

Practically, this makes sense. Panels degrade over time, weather conditions vary and solar farms don’t always hit their peak output. So, by installing more panels than is strictly necessary, operators can make sure they’re hitting the 49.9MW export limit more consistently.

Overplanting was sought in this case to address three factors:

- Solar panel degradation over time

- The maximum output of a solar panel is determined in laboratory conditions but the actual output of any solar panel in a field will be less than in laboratory conditions

- The combined effect of the configuration of the site and of fluctuations in the level of sunlight throughout the day/year.

The legal question: is that allowed?

The claimant in this case argued no. Or, at least, not unless it’s just to make up for panel degradation. The claimant pointed to NPS EN-3 and argued that overplanting should only be used to offset the natural decline in panel performance over time.

This wasn’t accepted by the Court. Mr Justice Eyre held that overplanting for reasons beyond that necessary to address panel degradation was not inconsistent with NPS EN-3.

In discussing the interpretation of NPS EN-3, the Court held that the starting point is that the interpretation of policy is a matter for the Court. The document is a statement of policy and is to be interpreted as such, rather than as if it were a statutory provision or a contractual term. In addition, the court must be conscious that the language of statements of national policy “does not always attain perfection. The language of policy is usually less precise”.

The Court held that the Inspector interpretated NPS EN-3 in the correct manner – he looked at the NPS as a whole and considered the nature, effect and purpose of overplanting. The Court noted that the purpose and context of NPS EN-3 are relevant when interpreting the NPS, and that part of the context is that the development of renewable energy technologies is a rapidly changing field (see paragraph 2.10.17 of NPS EN-3).

Additionally, paragraph 1.1.1 of NPS EN-3 is of particular importance, stating,

“there is an urgent need for new electricity generating capacity to meet our energy objectives”.

This underpins the flexible approach to interpreting NPS EN-3 and reinforces that it should not be read in such a way that would frustrate this core purpose. Mr Justice Eyre also considered the claimant’s argument in relation to footnote 92 of NPS-3, being that overplanting must be reasonable. Footnote 92 reads:

“Such reasonable overplanting should be considered acceptable in a planning context so long as it can be justified and the electricity export does not exceed the relevant NSIP installed capacity threshold throughout the operational lifetime of the site and the proposed development and its impacts are assessed through the planning process on the basis of its full extent, including any overplanting.”

Mr Justice Eyre held that footnote 92 does not impose a separate requirement and is clear that overplanting should be considered acceptable in planning terms if:

- It can be justified

- The export does not exceed the NSIP threshold (ie it must be below 50MW)

- The impacts of the development are assessed on the basis of its full extent (including the overplanting)

What does this all mean?

In short, we now have clarity on overplanting solar farms below 50MW – as long as they are within the export cap (ie 49.9MW) and the impacts of the development are assessed on the basis of its full extent.

This case is a reminder that planning law is rarely black and white. Policies are interpreted, not just applied, and sometimes, technical details (like how many panels you can squeeze into a field) can end up shaping the future of the energy grid.

Please click here to read the full judgment.

Melanie Grimshaw is a partner and Ryan Williams an associate at national law firm Mills & Reeve LLP