The growth in solar-based nationally significant infrastructure projects (NSIPs) across the UK is a topic that has been covered extensively here on Solar Power Portal, with many recognising the potential these huge projects hold in supporting the UK’s decarbonisation journey.

There can be no doubts that solar will play a pivotal role in the UK’s net zero journey. But although many instantly point towards rooftop solar installations, the true potential for solar can be seen in utility-scale developments.

NSIPs are huge projects of national significance in England and Wales that bypass the usual local level planning systems. These can range from new airport terminals to large-scale energy projects. For solar in this instance, any project that has a generation capacity over 50MW can be deemed an NSIP.

And, with the 373MW Cleve Hill Solar Park having entered construction in April, it is clear 2023 has been a successful year for NSIPs. But there was another major development announced in late October that mostly went under the radar.

As reported by Solar Power Portal, UK-based renewables developer Elements Green unveiled early-stage plans for a 1GW solar project in Nottinghamshire dubbed the ‘Great North Road Solar Park’. Interestingly, this development became the latest to be created in the county following Ørsted’s announcement in September that it would venture into the UK solar market via a 740MW project, also situated in Nottinghamshire.

To find out why so many large-scale solar projects are looking to call Nottinghamshire home and more details on Elements Greens’ NSIP, Solar Power Portal spoke with Mark Noone, project director for the Great North Road Solar Park.

‘We are going to be an exemplar for how you do this’

“We are going to be an exemplar for how you do this,” Noone starts, explaining that this makes up a big part of the organisation’s ethos. “We want people to understand that we are doing something pretty special here.

“As a developer, we’d like other developers to follow suit and give our industry a gold-plated feel.”

Elements Green is not the first to want to inspire other developers moving through the NSIP and development consent order (DCO) process and application. In fact, in a conversation with Solar Power Portal earlier this year, Gareth Phillips, partner at Pinsent Masons, said that its involvement in the Cleve Hill applications was a “A flagship for UK large-scale solar projects”.

Although Noone was unable to mention specific details of the project, he teases: “We’ve done a lot of interesting stuff that I’m not sure a lot of developers may have done.”

But perhaps the biggest question with this development, and maybe one that is at the forefront of our audiences’ minds, is how can this be developed? And why is Nottinghamshire gaining so many large-scale solar projects?

“The story of this one, really, is that the grid capacity was there. We made an application into an area with existing infrastructure in place so that we’re not plugging holes that are required in that infrastructure,” Noone says.

“This is where you’ve traditionally had a coal fired power station that has shut down. This is now a clear hole in the national grid infrastructure that we are plugging with something renewable where it once was polluting, meaning infrastructure build is minimised.”

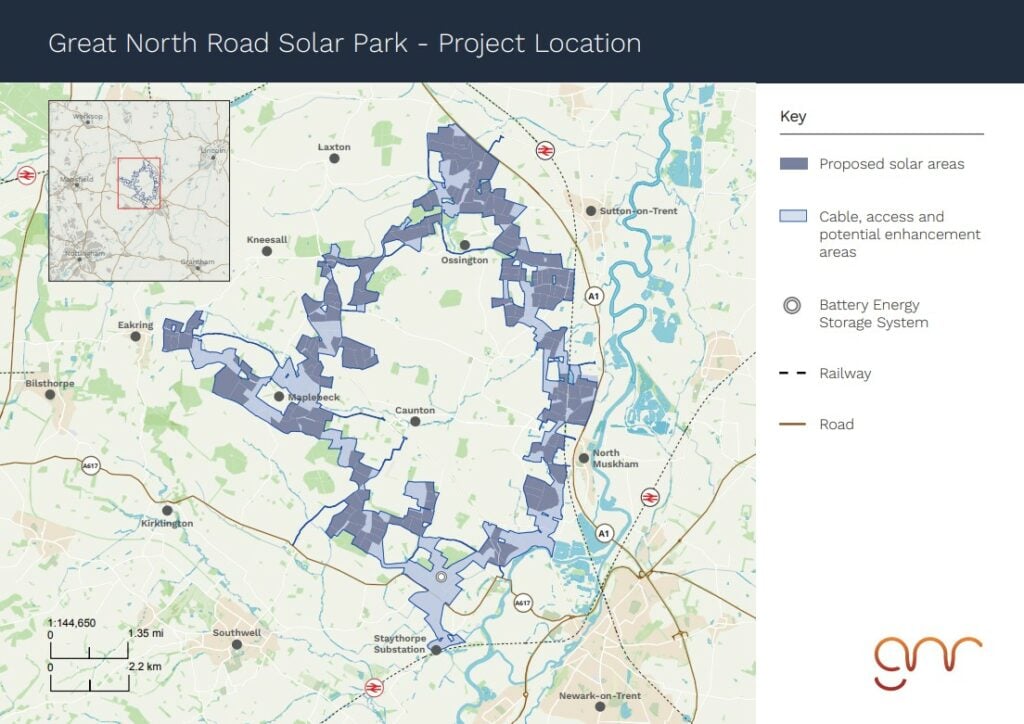

Not only is Nottinghamshire perfect in terms of the grid connections, but the actual design of this solar farm has been modified to seamlessly fit amongst the various transportation infrastructure and natural geography. This can be seen in the image below:

Commenting on the solar farm design, Noone says: “We thought why not do one big efficient solar farm? And rather than saying we’ll just impose one big monolithic block at that substation, we’ve taken a view that we could potentially go quite large in appropriate areas.

“To the side of the substation you’ve got the A1 motorway. You’ve got the East Coast mainline and the Great North Road. This is big corridor of infrastructure that ends in a big massive 20 acre National Grid substation. It is the right location for something big to be done.

“Rather than having this one big block we’ve thought about containing as much of the megawatts as we can up towards the A1 motorway. And then we can fit into the landscape appropriately where you’ve got some woodland cover, or you’ve got some nice flat topography or unobtrusive build areas for it. Spread it out so you’ve effectively you’ve got a seven-kilometre radius between one part of the site and another.”

Possible challenges in developing the 1GW NSIP

Upon being questioned on what some of the biggest challenges could be in the development process of the 1GW NSIP, Noone touches on an interesting aspect – archaeological findings.

“For this particular geography we are looking at, we’ve got archaeology acknowledge. That might be interesting because the Great North Road was a Roman road,” Noone says.

“If we came across a Roman villa, what could we do? It might be that you decide to run an excavation or archaeological project and we can go little bit further than a smaller local project could allow economically into something that could create some tourism (and therefore economic boost), rather than just covering up the find and moving on.”

This is something that can often be overlooked but is important, nonetheless. Nottinghamshire is a county steeped in rich history and, with the project being developed on a site well known for its historical roots, this could cause a bump in the development of the project. But as Noone says, this could become an opportunity for the developer.

One other prominent issue, as is with other solar projects of this scale, is public perception – something that can be alleviated via public consultations.

“We move on to popularity and public appetite and we’ve had interesting engagement so far with a mixed set of results. Some people are really crazy keen to do it and then some people are scared and that’s natural.

“We like to think that when people go into a consultation and come out the other end, they think that it is nothing like as bad as they thought it was. That’s a common thing in solar in general. I’m not necessarily saying that about this project, but in the solar industry, that happens a lot.

“It’s not to say everybody feels that way, it’s to say there’s a proportion of people walking through the door think this is going to be their world coming to an end and when they looked at what it is, they’re realising that actually quite a lot of things these guys are doing it quite positive.

“They’re going to clean up the air, they’re going to clean up the rivers, because there’s going to be less fertiliser and phosphates and sulphates on the land, the watercourses will be cleaner, there’s going to be more wildlife, they’re going to generate honey they’re going to do you know sheep are going to continue to be able to graze, so you’re going to have all sorts going on.”