Buried within chancellor George Osborne’s autumn statement last week was a pledge to protect energy intensive industries (EIIs). A politically-charged promise largely fuelled by the ongoing troubles of UK steel.

Osborne is to make EIIs exempt from paying levies on energy bills associated with renewable energy generation. Those charges, which cover the costs of the Levy Control Framework and pay for programmes such as CfDs, the RO and FiTs, are applied to each household and business energy bill.

The chancellor’s argument is that as they consume inordinate amounts of energy in comparison, they are disproportionately affected by them. EIIs have repeatedly complained about being hamstrung by such levies and called for protection.

However in making these industries exempt, the funding has to come from elsewhere. The Conservative government has made it abundantly clear that it will not finance renewable energy off its own back, so funding will instead be passed on to regular households. Quite how this aligns with the current DECC message of protecting bill payers at all costs is anyone’s guess.

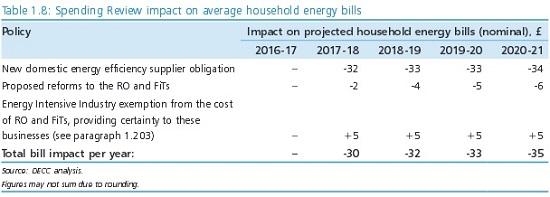

The precise costs to be added to household bills were not disclosed by Osborne at the despatch box last Wednesday, but were made clear in documents released afterwards.

As the chart shows, households will see their bills increase by £5 a year for the next four years to fund the exemption, at a total cost of £20. What the chart also reveals is that projected savings from “reforming” (read: all but closing) the renewable obligation and feed-in tariff will save households a total of £17 over the same period.

This represents an already distressing state of affairs for the renewables sector, but it’s about to get even more galling.

The government is not keen to directly disclose precisely what they will determine as an EII. HM Treasury passed on our requests for clarification to the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), claiming they deal exclusively with EIIs.

A spokesman for BIS told Solar Power Portal that the department would expect a “range of sectors to benefit” from the exemption in line with the European Commission’s Environmental and Energy Aid Guidelines, which set out what the EU considers to be an intensive energy user.

Previous consultations on the subject ran by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (who themselves would not comment on the subject, deeming anything autumn statement-related to be a matter for HMT) and BIS, state that the UK government would apply similar guidelines to determining an EII to the EC. This comprises a two-stage test held at both sector and company-level, based on their exposure to electricity bills.

The UK government intends to measure this based on industries with an electricity intensity of at least 7%, while other calculations will take into account electricity consumption, trade interests and their gross value added to the UK economy. In essence, it’s a complicated calculation to determine just what qualifies as an EII.

But, handily, the European Commission has aggregated a list of industries it considers intensive users of energy. That list, included on page 18 of the above consultation document, includes but is not limited to industries such as the mining of hard coal and the manufacture of refined petroleum products.

BIS could not confirm whether or not certain industries would be excluded from the exemption, and the whole policy is still subject to the UK receiving state aid clearance from Brussels. It expects that this might be received before the end of the year, at which point finer details would become clear.

But, on the face of it, it looks as if savings made from the feed-in tariff are being handed straight to large energy users to make sure they can survive the kind of difficult business environment the government is creating for domestic solar. It’s a galling prospect, and one that flies completely against any ‘the polluter pays’ principle put across in environmental law.