Solar panels at dusk by Magic K, via Pexels.

Yesterday, Spectator editor Andrew Neil Tweeted his disappointment in the UK’s solar power performance after it was announced that a coal-fired power plant was put on standby to provide more electricity.

One reason for the use of coal was that “Last Thursday the North Sea Link interconnector (between Britain and Norway) tripped losing 1.4GW of power just before lunchtime,” according to Charlotte Johnson, chief of staff & global head of markets at KrakenFlex.

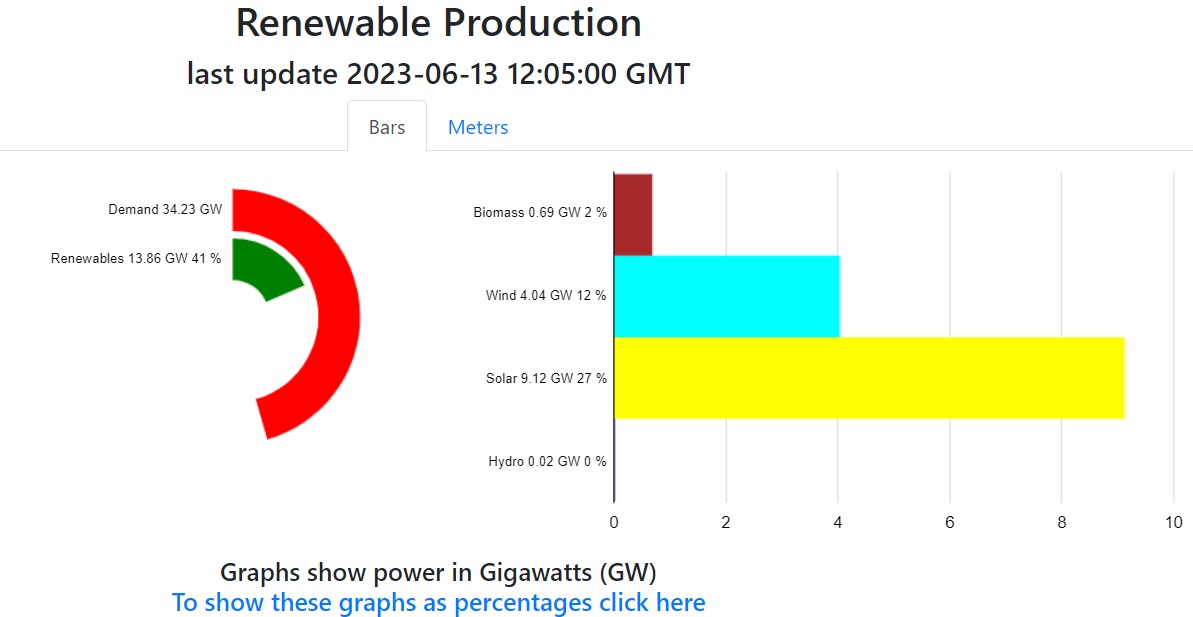

Being unaware of wider electricity supply problems, Neil seemed to be blaming the supply issues on the lack of solar output. Neil claimed that solar was “generating only 1.4GW (5%) despite 15GW installed capacity” without providing a source for this statistic.

Britain burning coal today to generate electricity after heatwave made solar panels too hot to work efficiently. But so far coal only minuscule amount of generation (under 1%). Solar generating only 1.4GW (5%) despite 15GW installed capacity, wind only 12%. Gas? Almost 50%.

— Andrew Neil (@afneil) June 13, 2023

Neil posted this at 09.17, yet at 09.35, the Gridwatch website was reporting that solar accounted for 6.6GW or 20% of electricity production.

The journalist had obviously been reading a Telegraph article which negatively reported on the UK’s renewable energy industry – part of a general trend in the paper's reporting. Recently, they have published a number of articles attacking the efficacy of heat pumps as a solution to the UK’s gas dependency.

In an article yesterday, Telegraph journalists Melissa Lawford, Chris Price and Benedict Smith claimed that higher June temperatures “made solar panels too hot to work efficiently”.

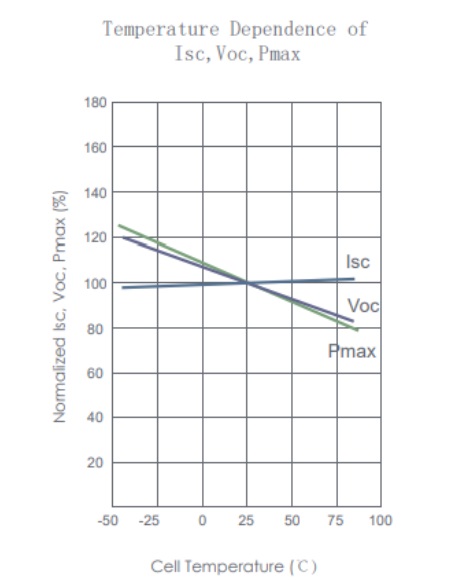

“Solar panels are tested at a benchmark of 25C. For every degree rise in temperature above this level, the efficiency is reduced by 0.5 percentage points,” the paper said.

Gareth Simkins, senior communications advisor at Solar Energy UK, says that this figure is an exaggeration. In emails to the Telegraph, Simkins told the newspaper that performance dropoff at higher temperatures is “not really a big issue”.

“Yes, the performance of photovoltaic panels does slightly degrade as the temperature rises – but you can say the same for thermal power stations (gas, coal, nuclear, etc).”

Simkins suggested that the Telegraph look at the performance models of various panels on the website of wholesaler Midsummer. “Picking one at random, let’s look at the Tiger Neo N-type 54HL4-B,” Simkins’ email continued.

“Its operating range is -40°C to +85°C. Performance falls by 0.3% per degree C, with 100% measured at 25°C with irradiance 1000W/m2 – standard terms. So even at close to boiling point, the power output would only be about 82% lower than standard conditions. At 30℃, 1.5% less, at 40°C, it would be 4.5% less. I understand that this performance is a little poorer than some other models, whose Pmax falls by about 0.25% per degree C.”

The Telegraph obviously decided to dispense with this information from industry experts to report that the figure for performance dropoff was twice as much (0.5%) as some of the better PV models available.

Neil then doubled down on his exaggerated claims by questioning why solar was producing “less than 10% of its installed capacity”.

So why in a heatwave are UK solar panels producing less than 10% of their installed capacity? https://t.co/3hGiKZ7mSH

— Andrew Neil (@afneil) June 13, 2023

As noted above, Neil was claiming that solar power was “generating only 1.4GW (5%) despite 15GW installed capacity”. By 12.05 that day, solar was generating more than 9GW according to gridwatch.co.uk.

Whether this is willful ignorance or just the normal kind, these kinds of pronouncements from big media figures underscore that there is a general lack of knowledge about how renewable energy works.

Of course solar doesn’t produce its full capacity most of the time, but suggesting that it only produces 10% of its total output on a normal day is a blatant exaggeration.

In a statement, Solar Energy UK also said that, “More solar power is produced in the summer than any other time – regardless of how hot it gets.”

“Clearer skies, longer days and more sunlight add up to mean that significantly more power is produced overall during the summer. With over 14 hours of daylight each day between May and August, it's a great time to generate renewable electricity – which can also be stored and used when less is being generated,” the organisation said.

“The idea that solar panels wilt in the heat is a gross and fundamental misapprehension,” Solar Energy UK concluded. Alastair Buckley, professor of organic electronics at the University of Sheffield, concurred with Solar Energy UK, saying: “It’s not actually a big deal. High temperatures only marginally affect the overall output of solar power – it’s a secondary effect. If it’s sunny and hot, you are going to get good power output. It doesn’t fall off a cliff.”

Buckley was also quoted in the Telegraph article, but told Current± that “the context of the conversation that i had with [The Telegraph] has been manipulated,” though “the facts in the quote are true to the level of precision that I intended.”

“Historically and today 0.5%/degC temperature loss in efficiency is the rule of thumb value that I would say is accepted for Si solar cells. Obviously manufacturers are working to improve this and the most modern cell tech has lower coefficients. But of course the GB installation base is not all new modules so i'd stand by 0.5 as a sensible order of magnitude number to explain the effect of temperature on panel efficiency,” Buckley added.

“25 degrees is the temperature at which standard tests are made on module efficiency. It's not a special number in terms of the overall performance of a panel. If it's cooler than 25 degrees then the efficiency goes up,” Buckley concluded.

Solar PV technology is still improving in its efficiency. Some n-type TOPCon PV cells are now reaching over 26% conversion efficiency, while experimental PV technology like that made by Oxford PV recently set a 'new world record' for the efficiency of a commercial-sized solar cell with 28.6% conversion efficiency. This is higher than the efficiency of mainstream silicon-only solar cells, which average 22–24%.

Ten or more years ago, it was common for renewable energy naysayers to be negative about the potential of renewable technology to provide the majority of the UK’s energy needs.

Yet in the last year, wind has started to provide more electricity than burning gas for the first time, and renewable generation cut the UK’s gas consumption by 85TWh from October 2022 to February 2023.

The trends are clear, yet the public is still woefully uninformed about the positive benefits of the renewables industry. This lack of public understanding probably makes it harder to recruit workers with the skills that the renewables industry needs, and it means that voters will be confused in discussions around energy security – one of the biggest topics in UK politics in 2023.

The public are generally supportive of the renewables industry even if they don’t understand the technical questions involved. 74% of the public agreed in 2022 that renewable energy benefits the UK economically. 83% of people in the UK are worried about climate change, whilst the number of people “very concerned” rose by 6% to 45%.

It’s time to turn this enthusiasm into broader knowledge through education and public relations campaigns from the renewable energy industry. Too often we are talking to just ourselves, but we also need to bring the general public along with us, because they are the solar installers, wind farm engineers and data scientists of the future.